Early days of dialysis and transplantation in Seattle

Linda Johnston has much to celebrate, which she does every year on September 15th. This year, she celebrated the 55th anniversary of having received her first kidney transplant when she was only 16 years old. She is very aware of her good fortune in having grown up in the Seattle area during the 1960s, where the innovative research and healthcare at the University of Washington provided her with the ability to not only survive her illness through dialysis and kidney transplantation, but also laid the foundation for many decades of good health.

Seattle, the place to be

Linda attributes much of her health and vocation as a medical doctor to UW transplant surgeon Dr. Tom Marchioro, who guided and inspired her as a young kidney patient. She was the youngest dialysis patient and kidney transplant recipient at UW. She thinks she may be the longest living patient on replacement therapy, having started dialysis on December 4, 1969. At the time, Dr. Belding H. Scribner, the head of the UW Nephrology Division, was working on groundbreaking research related to dialysis and the kidney. “Seattle was the only place on the planet that had the help I needed,” Linda says.

Linda looks on the bright side and counts her blessings, notwithstanding her arduous health journey since her kidneys began to fail in 1966 when she was only 12 years old. Not everyone had access then to the lifesaving treatments of dialysis and transplantation. Growing up in Bellevue, WA, her family doctor didn’t realize what was causing her illness until an observant nurse lab technician noticed albumin cast in her urine specimen. She was immediately referred to well-known Seattle nephrologist Dr. James Burnell for a kidney biopsy.

Burnell was one of the world's first kidney specialists. He helped develop many of the hemodialysis advances that emerged from Seattle in the 1960s. After the biopsy results came back, Dr. Burnell informed her parents that there was nothing to be done; Linda would not recover kidney function and they should prepare themselves for the inevitable, she would not survive. Linda’s parents chose a second opinion from the University of Washington, where they met Dr. Tom Marchioro, transplant surgeon, and Dr. Robert Hickman, pediatric nephrologist and inventor of the Hickman catheter. [“The Hickman catheter instantly transformed transplant care,” said Dr. Rainer Storb, a pioneering transplant physician and one of the founding scientists of Fred Hutch.] The UW doctors offered an alternative plan: “She might die, but let's see what we can do.” That decision allowed Linda to enter the system of Northwest Kidney Centers, known at the time as the Seattle Artificial Kidney Center, where she applied for dialysis care.

Seattle was the hub of early dialysis treatment, with groundbreaking research conducted by Belding Scribner and a team of doctors dedicated to providing care to those who would otherwise have had no hope of survival. The Seattle Artificial Kidney Center at first declined Linda’s request to begin dialysis. There was grave concern that her youth indicated she would not be able to handle the rigors and discipline of the process. They wanted patients with the best possible survival outcomes to participate. Additionally, during the early days of the kidney center, there was no insurance or government money supporting patients. As a condition of acceptance, each had to bring their own funding because of the limited resources available. Fundraising was common to assist with payment. Patients accepted for dialysis would never be turned away if they ran out of money. Therefore, the center could only afford to accept a limited number of patients and Linda did not qualify.

School days

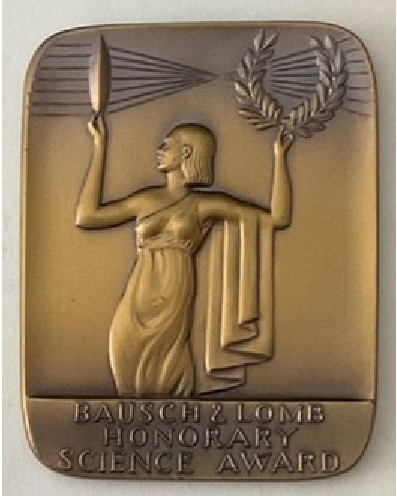

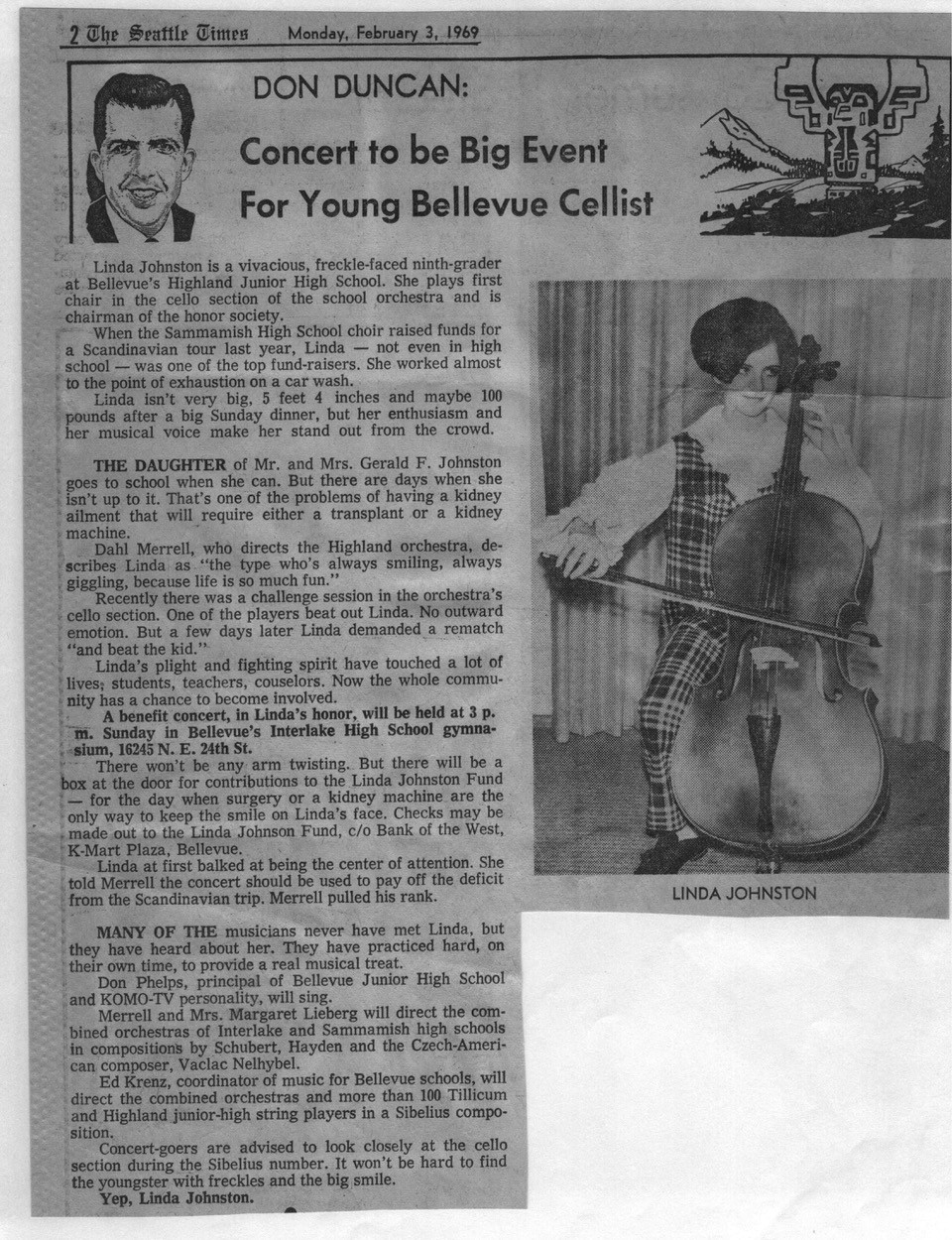

In spite of her illness, Linda was an active young person. She began playing cello when she was 10 years old, when the instrument was larger than she was, carrying it home from school each Friday for weekend practice. By ninth grade at Bellevue’s Highland Junior High School, she was first chair of the cello section in the school orchestra. She was also the chairperson of the school honor society. Linda excelled in science as well, and at Sammamish High School, she won the prestigious “Bausch & Lomb Honorary Science Award,” given only to those who show the highest achievement and rigor in science and math classes, and offer positive contributions to their school and the larger community.

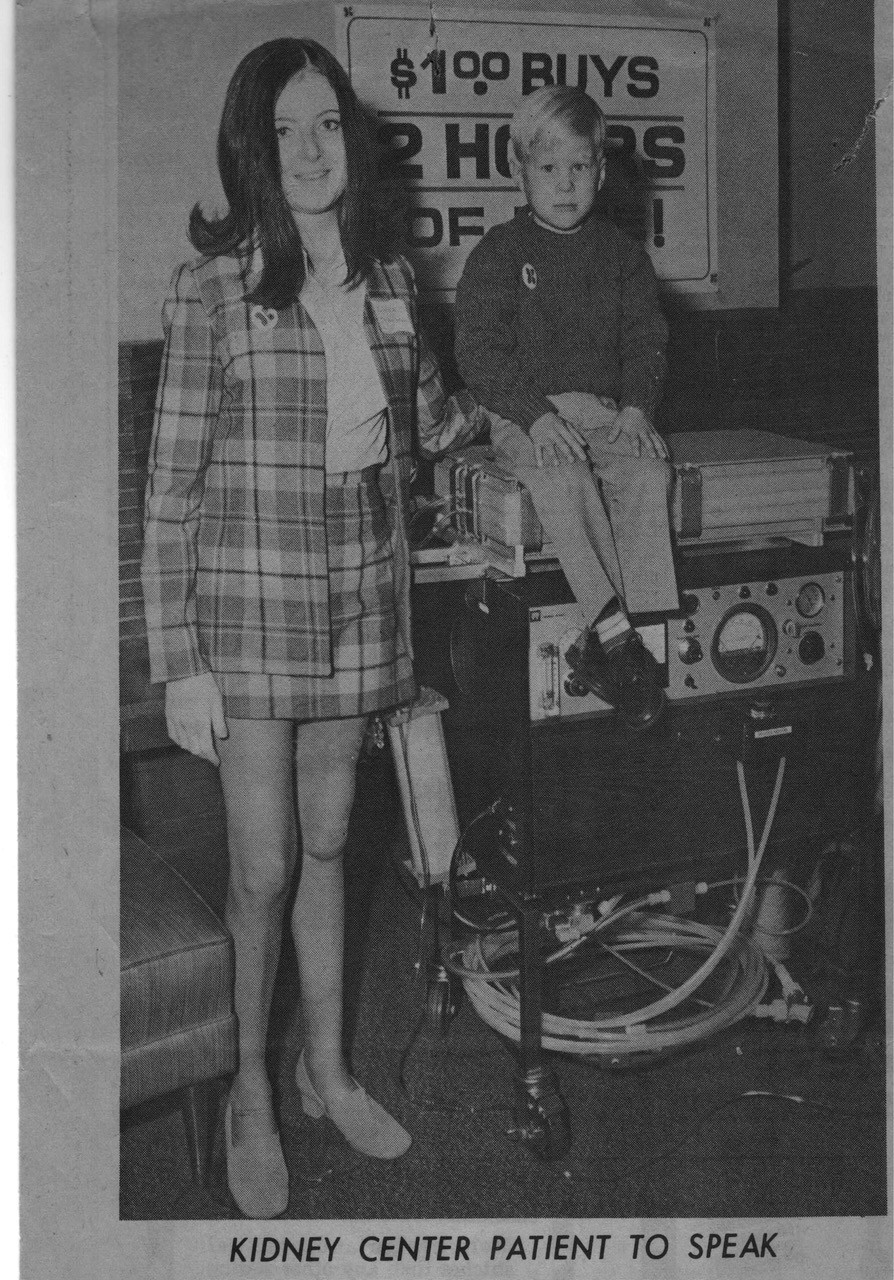

Linda loved learning and attended school when she felt up to it, but there were days when she was too ill. The Johnston family’s friends were aware of her failing kidneys and subsequently created local fundraisers to benefit the “Linda Johnston Kidney Fund.” Interlake High School and Sammamish High School planned a concert in her honor to raise funds for medical expenses. Students, teachers, and the community wanted to chip in. Linda thought the concert funds should go toward school trips instead of to her, but the orchestra director insisted, according to an article written in the Seattle Times. Besides concerts, neighbors and friends participated in cookbook sales and coupon clipping drives to help raise money. Linda still recalls the bags and bags of clipped and bundled coupons that accumulated around their home from the collections.

I have never met you before, but I know your urine

Under the care of the UW doctors, Linda faithfully collected 24-hour urine every day for 10 months to monitor her kidney function. Dr. Scribner used the urine for research to observe the kidneys' gradual decline in someone with glomerulonephritis. By this time, she was 14 years old. The arduous schedule of daily urine collection for Dr. Scribner exemplified her persistence and dedication.

“I collected all the urine each day, then measured the amount and saved a vial of urine from that whole daily collection. Once a week, driven by one of my parents, I would take 7 vials to the lab in the University of Washington Hospital. Dr. Scribner was studying how the decline of kidney function occurred over time. I was the perfect case study because my kidneys were slowly failing, and I was willing to collect the necessary urine samples over a long time. Some years later, when I finally met Dr. Scribner, he said, “I have never met you before, but I know your urine!””

In the summer of 1969, Linda became much sicker. She recalls the Thanksgiving meal that year when she was so ill she couldn’t eat the special meal and could barely sit in her chair. For several weeks prior, she had been having severe pain in her chest and had lost vision in one eye, but she did not tell anyone about these drastic changes. Seeing her health decline, her parents took her to University Hospital, now UW Medical Center-Montlake, and the hospital admitted her as an emergency. They discovered that the chest pains were from pericarditis and the vision loss was from optic nerve edema - both serious consequences of renal failure. The hospital transferred her to Swedish Hospital, where they placed an emergency Scribner cannula in her right forearm.

Doctors typically allowed the cannula to heal for 6 weeks before starting dialysis, but her condition was so advanced and life-threatening that they started her on dialysis after only a few days. “That was as close to dying as I ever came, but fortunately, I was pulled back from the brink!” Linda said.

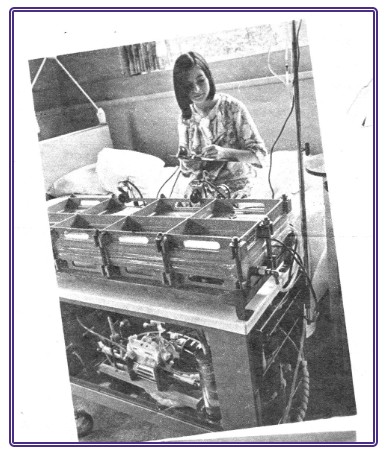

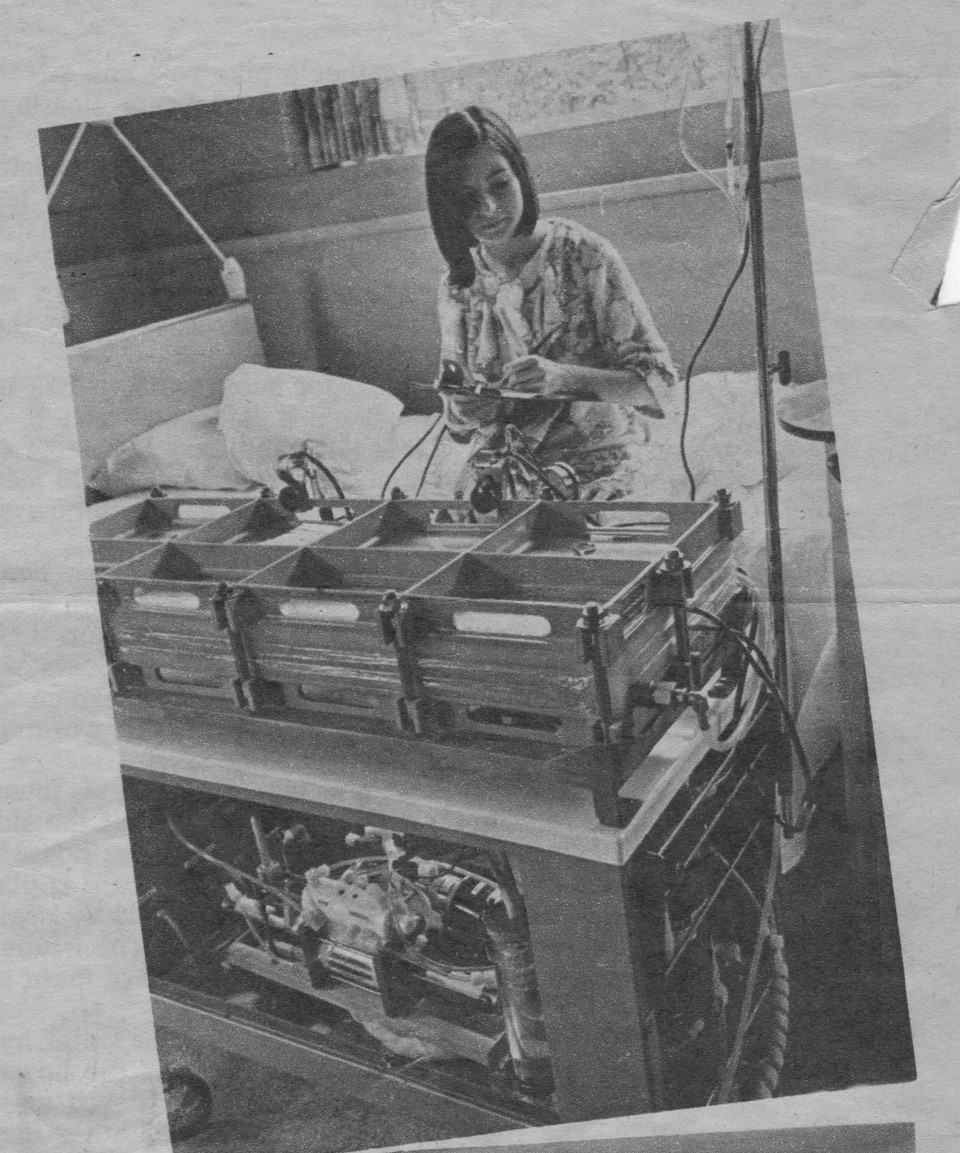

On December 4, 1969, Linda began dialyzing 3 times per week for 8 hours each visit. As part of this process, she took manual readings from the machine every hour. She did not see it as a burden in the midst of being able to live and go to school.

“I can say I was never afraid of the doctors, the dialysis machines, or even my illness. It was all just the hand I had been dealt, and most of the time it was an adventure. I didn't see it as something groundbreaking or innovative. It was more, how long am I going to live?”

Changing the paradigm

In June 1970, her parents decided they would like her to dialyze at home so she could sleep during treatments, but they were told they would need to buy the expensive dialysis machine. Because of her father, Gerald Johnston’s initiative and creative problem-solving, which characterized his entire career, he convinced the center to lease the machine to them since Linda was hoping for a transplant and wouldn’t need the machine forever. Leasing dialysis machines had never been done, but thanks to Linda’s dad, it is now a common practice.

A bedroom in the basement of their Bellevue home became her dialysis center. “The first night, my poor dad, he was so worried he couldn't sleep at all. He was just so worried. He set up a buzzer, like an alarm bell, and threaded the wires out of the window up to their bedroom, and I had the buzzer so he could sleep more comfortably, knowing that I could buzz him if I ran into problems.”

In September 1970, when Linda was 16 years old and had been on dialysis for 9 months, she received a new kidney. The living donor was her mother. Linda’s father proved again that he could think outside the box when Blue Cross preemptively declined to pay any of the costs related to her mother’s kidney donation. They deemed it was “not medically necessary” and stated that her donation was "elective surgery” and therefore not covered by insurance. Linda’s father fought this decision tooth-and-nail and prevailed. From then on, insurance companies, starting with Blue Cross, covered organ donation costs.

“Of course, over the many decades of the development of dialysis and transplantation, there have been many unsung heroes. Through behind-the-scenes efforts, often anonymous, and standing away from the limelight, they have contributed so much to allow the frontline people, like the doctors and hospitals, to advance these lifesaving treatments. I am proud to say my father is certainly among that group.”

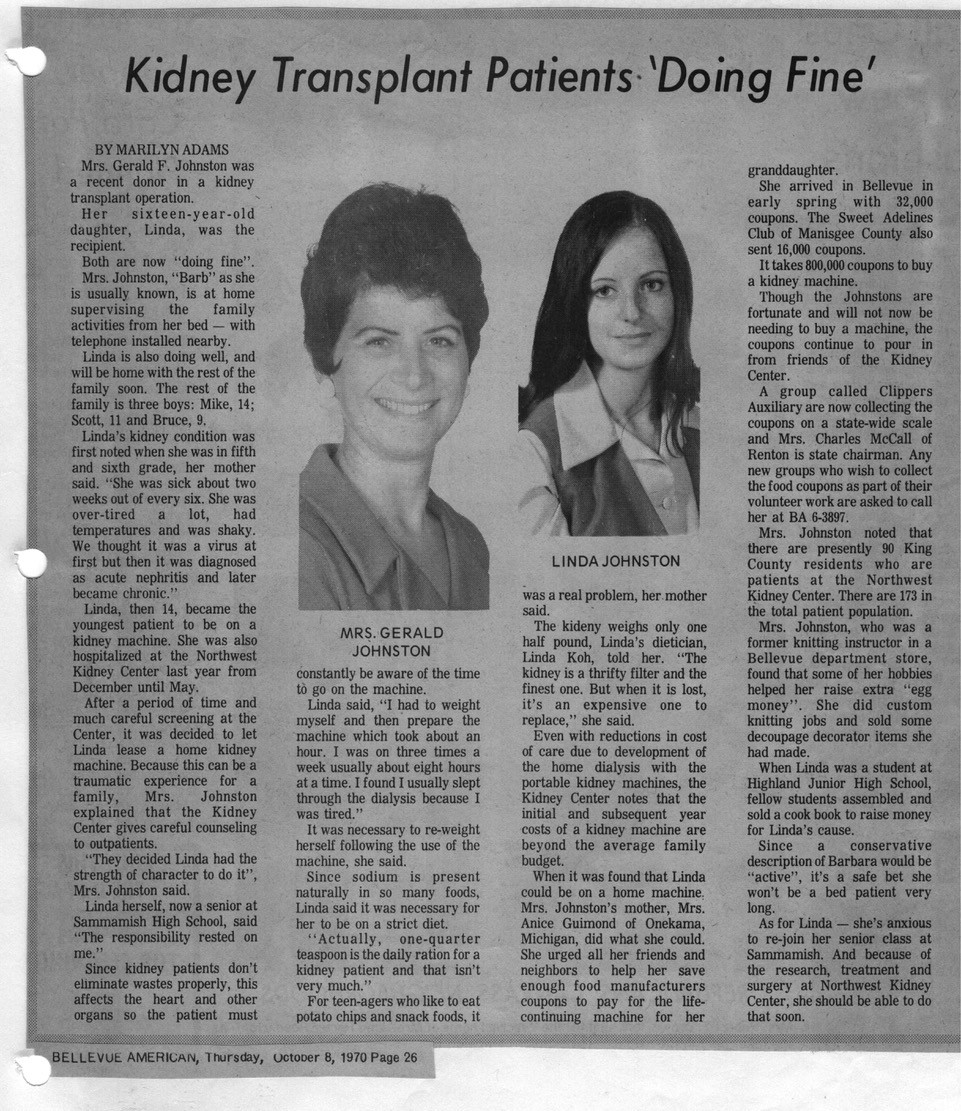

Mother-daughter transplant surgery is big local news

The Bellevue American newspaper wrote articles about the ground-breaking medical event and how Linda and her mother were recovering from their surgeries. Always grateful while she was on dialysis and post-transplant, Linda participated in public speaking on behalf of the Northwest Kidney Centers to raise awareness and funds.

Three months after surgery, on September 15, 1970, Linda returned to high school, and 3 months after that she began working at a fabric store for $1.60 per hour. She worked at the store full-time through high school and college. Linda had taught herself to sew at age 11, and it is still an important avocation in her life. Before earning a wage at the fabric store, she would use every tablecloth, discarded piece of clothing, or curtain for sewing material to satisfy her creative efforts. “I have always had great comfort and solace in the creative process with the medium of fabric and fibers. Many a day before a big test or after a particularly difficult day, I could go into my sewing room to create something beautiful and that would soothe all the world’s cares away,” Linda said. The money she earned at the fabric store funded a 5-month solo trip to Europe between high school and college when she was 17 years old. She managed her health on her own while she traveled. When she returned from her trip, having been inspired by Dr. Marchioro, Linda enrolled in college at the University of Washington, and later entered the UW School of Medicine.

“Going to medical school was absolutely the thing I wanted to do. Even if, let's say, I didn't survive long after, I still would have said, I'm glad I did it. That's how I wanted to spend my time. And it was a fantastic experience. I really loved it.”

Adult life and a second transplant

Linda began a private medical practice in California in 1981. She was only a few years into her new practice when her transplanted kidney began to fail. It had kept her alive for 14 years. For months she traversed the uncertainty of declining health, juggling her own patients, and barely qualifying for health insurance while she waited for a new kidney to become available. She was worried about needing to go back on dialysis, remembering how physically draining it was, but she was prepared to do so. On the last day, when she had no more strength and a shunt had already been placed, the phone rang with news that a kidney was available. She went to the hospital on Thursday, and on Friday she had a new kidney.

That was in 1984, and after 41 years it is still going strong! It is one of the unusual instances where a second kidney has lasted longer than the first. And as a bonus, Linda no longer has to significantly restrict her diet. The world has certainly changed since those early days of dialysis and transplantation. When Linda’s father traveled to Venezuela in about 2012, he caught a taxi ride from a driver who was exceptionally talkative and joyful. Lifting his shirt to show off a recent scar, the driver exclaimed, “I am so happy! I've had a kidney transplant! Do you know anything about that?” Linda’s father smiled and replied, “You have no idea!” Once a groundbreaking medical miracle in the 1960s and 70s, kidney transplantation has become more available and less risky. The number of kidney transplants done in 2024 was 27,759. Despite that number, 100,000 people are on the waiting list for kidney transplantation.

Linda now lives in Texas, having retired after 43 years as a solo private practice medical doctor. She spends her free time making beautiful, large-scale art quilts and needlepoint hangings. She walks in her neighborhood, and on rare occasions shares her story with friends, telling them of her kidney transplant and her good fortune. They are stunned at how long her kidney has lasted and how healthy she is. Linda has been an avid world traveler since her first trip to Europe at 17. She has visited every country she has desired to see. When Linda was 54 she met and married her husband. They recently celebrated their 17th wedding anniversary. Linda likes to say, “He wasn't actually the man of my dreams because I couldn't dream that good.”

When asked if she has any advice for young people facing health challenges, Linda quotes Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr. (1809–1894), the physician, professor, and poet who said, "The best way to live a long time is to have a chronic disease and take very good care of it." Having an illness is a little blessing, she says. “You have the awareness early so that you don't lose the health that your body is endowed with.”

A life of gratitude: An illness and its blessings

“Throughout one’s life, every person has to constantly maintain a balance between living for today and saving for tomorrow. With my experiences, it is easy to imagine that I had my thumb on the scale in favor of living for today. To a certain extent that is true and accounts for my urgency to travel to Europe at age 17 and to being accepted to medical school at age 20. Yet despite all the evidence to the contrary, mixed with that was my deeply held commitment to and confidence in a great future. The mere fact that I wanted to go to medical school speaks to that confidence and my willingness to invest in that future. At age 71, I can reflect back on my very blessed life of excellent health, with a rewarding career serving patients, travels all over the world, enriching experiences beyond number and an avenue of creative expression. My early confidence in my future was not misplaced.

“Every year since, on the anniversary of my transplant, I made it a point to visit or write to Dr. Marchioro until his untimely death in 1995. I had such unbounded gratitude for my new lease on life that he and others had given me that I made it a solemn practice to celebrate that date with appreciation to him. For many years I was burdened by the question of how could I ever thank all those people who had worked so tirelessly and diligently to preserve my life, as embodied in and exemplified by Dr. Marchioro. I finally got an answer to the perplexing issue. When I was 32, the anniversary marked the time I had had a kidney replacement for as many years, 16, as I had had my original set. I was thinking about what to write in my letter to Dr. Marchioro, including that issue. In a flash, I flipped the script. I had been in medical practice for several years so I asked myself what would I want from my patients to thank me for helping them achieve health? The answer was easy - all I really wanted, the only thing that had any value to me at all was for each person to fully live and enjoy their newfound health and vitality! Nothing else was important. Finally, after 16 years, I had my answer! The best, in fact the only, way to thank Dr. Marchioro and everyone else involved in my care was to live my life to the fullest with joy, vigor and enthusiasm! In fact, unbeknownst to me, I had been thanking him all along by enjoying every single day of my life. And I still do!”

Story by Krista Forsyth Fisher - UW Division of Nephrology